#TBT - The cowboys and gargoyles of cyberpunk's virtual reality

Before virtual reality was well, a reality, it electrified the imaginations of many modern innovators in the realm of fiction. The cyberpunk literature of the '80s and '90s predicted many aspects of technology today. Multinational mega-corporations that defy national governments, inscrutable AIs, information warfare, constant surveillance...sound familiar? Of all the concepts that spread from the page to the technology all around us, the virtual world of cyberspace has been one of the most pervasive.

You can find more videos on current tech topics on our video page.

Virtual reality technology develops slowly but surely, but as with any emerging tech sector, skeptics scoff and roll their eyes at each development that doesn't meet a completely immersive standard. It's an "are we there yet?" attitude. But we all know that there is a destination. One that's in equal measures fascinating and disturbing.

A collective hallucination

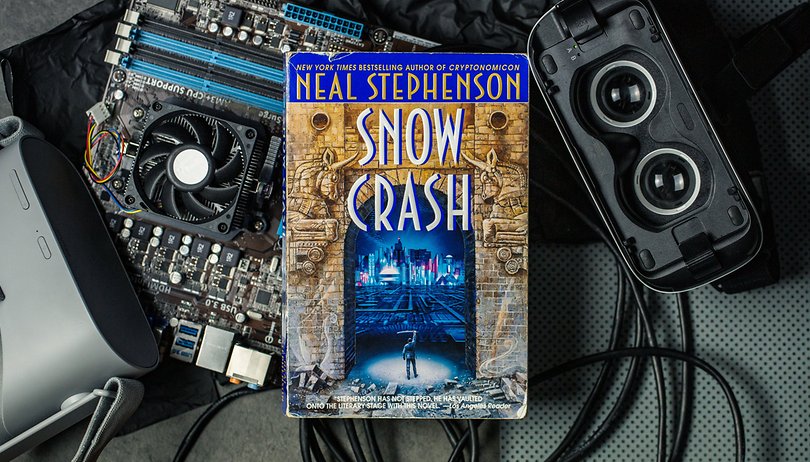

That destination was described in cyberpunk science fiction, most significantly (but by no means exclusively) in two works, William Gibson's Neuromancer (1984) and Neal Stephenson's Snow Crash (1992). In both cases, the heroes and villains perform investigations and daring heists in a persistent virtual world that anyone with the right technology can access. Shopping malls, public spaces, nightclubs, corporate enclaves and workspaces are all present in the digital landscapes. In these stories, personal VR technology is relatively widespread but the protagonists are often misfit hackers whose special skills in manipulating the virtual world grant them the power to take on the bloated corporations in a world where money, technology and intellectual property have made companies more powerful than any state.

"The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games [...] Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts ...A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding . . ." - William Gibson, Neuromancer.

Gibson's concept of cyberspace, first described in his earlier story collection Burning Chrome, became adopted as a term for the wider Internet as a whole. He also called it the matrix, a name that was picked up again and popularized by the iconic 1999 film of the same name. The technology described doesn't look a whole lot like VR today, in fact, to get into cyberspace, users connect with decks via 'dermatrodes', plugging their bodies in but actually remaining physically stationary the whole time. In these stories it's not only possible to embody yourself in the matrix, but even inhabit someone else's body, 'riding' them. The free-wheeling hackers who take on these kind of jobs are known as 'cowboys', to stress the wild west nature of the setting.

In Snow Crash, written 8 years later the shared VR space, known as the Metaverse, is a little more familiar. Users enter via devices resembling modern VR headsets and also remain aware of their real-world surroundings at the same time. Stephenson's Metaverse appears as a city (real estate owned entirely, of course, by a corporation, and thick with advertising) in which user avatars (a term for virtual representations of users popularized by this novel) can appear as anything, limited only by size.

"So Hiro's not actually here at all. He's in a computer-generated universe that his computer is drawing onto his goggles and pumping into his earphones. In the lingo, this imaginary place is known as the Metaverse. Hiro spends a lot of time in the Metaverse. It beats the shit out of the U-Stor-It.

Hiro is approaching the Street. It is the Broadway, the Champs Elysees of the Metaverse. It is the brilliantly lit boulevard that can be seen, miniaturized and backward, reflected in the lenses of his goggles. It does not really exist. But right now, millions of people are walking up and down it. The dimensions of the Street are fixed by a protocol, hammered out by the computer-graphics ninja overlords of the Association for Computing Machinery's Global Multimedia Protocol Group. The Street seems to be a grand boulevard going all the way around the equator of a black sphere with a radius of a bit more than ten thousand kilometers. That makes it 65,536 kilometers around, which is considerably bigger than Earth.

[...]

Like any place in Reality, the Street is subject to development. Developers can build their own small streets feeding off of the main one. They can build buildings, parks, signs, as well as things that do not exist in Reality, such as vast hovering overhead light shows, special neighborhoods where the rules of three-dimensional spacetime are ignored, and free-combat zones where people can go to hunt and kill each other." - Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash.

For some, the lure of the Metaverse is so addictive and preferable to real life that they go about permanently connected to their headsets and peripherals, earning them the nickname 'gargoyles' for their grotesque appearances. But is it empowering, liberating, even. You can be anyone, and in a sense realize your dreams. Hiro Protagonist of Snow Crash (yep) lives in a grotty storage container and can barely afford material possessions, but in the Metaverse he can be someone - cool, respected, powerful. Here VR can provide not just escapism from poverty and oppression, but also the means to fight it.

Not just a game

For all that the consumer-facing applications of virtual reality nowadays are focused on video games, and the activities within the fictional metaverse have the trappings of video games, like violence, intrigue, alternate appearances and personalities, cool outfits, weapons. Cyberpunk doesn't paint a picture of a gamer's paradise. In fact, games are somewhat looked down upon. The action in the Metaverse has real consequences, the stakes are high, and what goes on in virtual reality is real life, just as real or even more so than when you're not plugged in.

"Amusement parks in the Metaverse can be fantastic, offering a wide selection of interactive threedimensional movies. But in the end, they're still nothing more than video games." - Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash.

Likewise, modern virtual reality blurs the line between video games and more serious applications. Not just because of how VR simulations are used in medicine or industry, but because of how fictions like the matrix and the Metaverse inspired the creation of games and social spaces alike, often by the same people. Snow Crash influenced the development of Quake and it's networked 3D environment, for example. In my discussion with the creators of Somnium Space, who are building virtual real estate reminiscent of the Metaverse, they cited a VR version of Quake as an inspiration to the possibilities of a (less violent) world of VR interaction. Second Life also comes up frequently in discussions, as creators Linden Lab develop their VR world Sansar.

Shared persistent social VR spaces, including shops, homes and nightclubs and of course, play areas, are a kind of convergence of social media, gaming and business in a new kind of Internet, one that's slow in coming. But it's being built, in virtual reality and augmented reality too, in many cases by geeky entrepreneurs who read these books and were captivated by the magical, transformative potential of the fictional Metaverse.

In many ways, we're already living in a non-VR version of the Metaverse, thanks to innovations in mobile telephony that cyberpunk didn't guess at.

Skipping a crucial step

In their envisioning of a connected world over computer systems, the pioneering cyberpunk authors failed to predict a critical step in the evolution of cyberspace - the now ubiquitous smartphone. A world of virtual selves, fake and blurred identities, financial intrigue and crime, corporate and political espionage, social engineering, addiction and alienation is all in the cyberspace of the here and now, but we don't experience it through VR goggles or bodysuits...instead, it's via the smartphone display in our pockets. And yet, while not quite as immersive, that doesn't make what happens in the cyberspace through our smartphones any less impactful on our socio-economic lives, our physical and mental health, and the environment.

Our world has moved beyond neon and chrome, If there's a popular cyberpunk fiction that applies its legacy of technological fascination and skepticism to our connected world of rounded edges and social media 'like' obsessions, its something like Black Mirror. But that doesn't mean that the past works of Gibson, Stephenson and co. have nothing to teach us.

A warning for today?

Cyberpunk is enjoying something of a revival in pop culture as of late, but just like the protagonist of the novels, we have to recognize the difference between entertainment and 'reality', expanded though the latter may be. Steven Spielberg's big-screen adaptation of Ready Player One had some trappings of cyberpunk, with a hero that fights in virtual reality against an all-powerful corporation, but it's also a hyper-consumerist fantasy, battling for the right to enjoy your favorite entertainment without too much advertising.

Likewise, CD Projekt RED's upcoming Cyberpunk 2077, while not a VR game, throws back to aesthetic and themes popularized by Snow Crash and Neuromancer and even features Keanu Reeves, the star of cyberpunk films like The Matrix trilogy and the (not so great) William Gibson adaptation Johnny Mnemonic. The company famous for "choice and consequences" in The Witcher RPGs will likely have a few things to say about cyberpunk's socio-political themes, but it's all too easy to beat all your enemies and save the day in the controlled environment of a video game, which is meant to be an empowering fantasy.

In the real world, it's a lot more complicated, and individuals have much less power. When it comes to virtual reality specifically, one can see that it's already on a trajectory, like many so many other technologies, from the preserve of thinkers, scientists and enthusiasts to being co-opted into systems of surveillance and control (however benign you may think) by large corporations. Consider Facebook, which evolved from a college "hot or not" site to a global empire dominating communication, news, image-sharing, advertising and via Oculus, virtual reality. And now, it will even have its own currency. The dystopian nightmare of the '80s is just a fact of life now. And yes, I point this out even though I'm enthusiastic for the technology Oculus offers.

Virtual reality can be a magical, liberating technology for many. Just ask those using it to make artwork, or even just the chance to express themselves in VRchat, for example.

Discover the modern Metaverse population in this video by iiwii Gaming:

VR can take us outside of our bodies, open us to experiences otherwise out of our reach, be empowering in totally new ways. On the flipside, it could evolve into a tool of distraction even more powerful than the smartphones that many decry as 'zombifying' society.

Is the future one where we'll strap on VR headsets and turn into cyber-samurai, fighting the megacorps within the virtual worlds that they built? Probably not. The reality is more insidious and less glamorous. But Neuromancer, Snow Crash point at a world where we can take control of the technology that's used to control us and poison the environment, and instead us it to liberate us. And that's an attitude worth reviving.

How do you think virtual reality today compares to how we imagined it in fiction? Share your recommended reading with us in the comments!

Source: Snow Crash, Neuromancer